The value of religious community archives is much more than preservation of the history of a particular religious community. They are also an important resource for mission and heritage formation in health care, education and social-service ministries that are, in large part, led today by laity. Such is the case with the Sisters of Providence and Providence Health & Services (PHS), which was born of the Sisters’ early work in the American West.

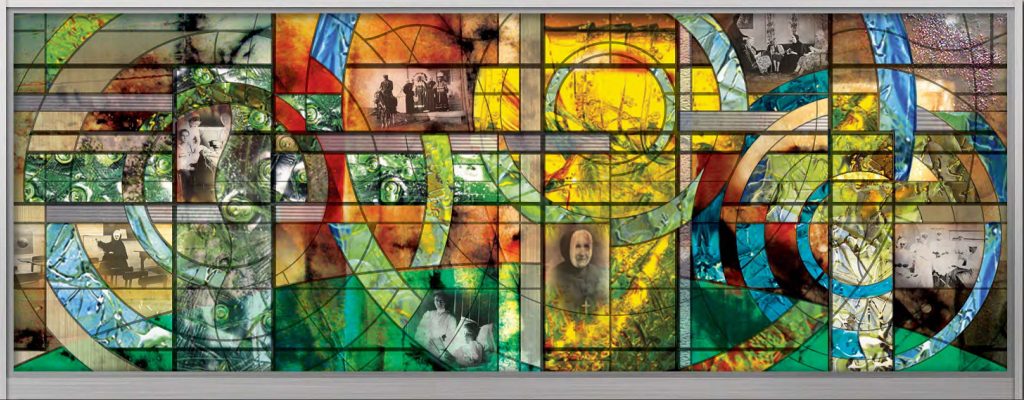

Stained glass mural, incorporating images from Providence Archives collections, reflects the heritage of the Sisters of Providence in the West. Dedicated in 2014, the mural is prominently displayed in the main entrance of Providence St. Joseph Health system office in Renton, Wash. It replicates one in the International Center of the Sisters of Providence in Montreal.

The Sisters of Providence were founded in 1843 by Ignace Bourget, Bishop of Montreal, and Blessed Emilie Tavernier Gamelin. Today this international congregation is celebrating its 175 th anniversary. Laity have always been active participants in the ministries of the Sisters of Providence and have shared the

Sisters’ charism and spirit. In earlier years, these values were absorbed simply through the experience of the Sisters’ personal actions and service in multiple roles. In the late 1970s, as Sisters filled fewer roles and became less visible in PHS ministries, mission effectiveness programs were developed in response to a movement for hospital staff to relate mission to all facets of their daily work. Mission statements and core values became part of the work culture. Today, these programs have developed into full- fledged, system-wide mission and heritage formation programs ranging from a daylong orientation to annual weeklong celebrations and several-month and multi-year programs. The foundation of each of these programs is the history preserved and made accessible by the archives.

At Providence Archives, Seattle, we host archives tours for formation groups, write interpretive and educational articles in our departmental newsletter, create relevant exhibits, and make presentations at formation workshops. Leaders rely on the archival collections for past and not-so-distant history,

photographs and artifacts for spiritual reflections, insight into past responses to similar contemporary events, examples of the lived core values, and for teaching the Providence charism, mission and heritage. At no time is this more important than today. As all religious communities are challenged by a decrease in membership which has affected their ability to fully participate in their ministries, they look for alternate means of sponsorship. With each merger, affiliation and sponsorship model, the heritage of each founding community or organization has to be sustained and imparted to all who work in that

ministry. Providence Health & Services is now part of Providence St. Joseph Health, created by PHS and St. Joseph Health. It includes the heritage of the Sisters of Providence and two other religious communities, Little Company of Mary and Sisters of St. Joseph of Orange, as well as six other affiliated health systems.

Sister Susanne Hartung, SP, Chief Mission Integration Officer, and Mike Butler, CEO Providence Health & Services, participate in a mini-pilgrimage at a statue of Blessed Emilie Gamelin, foundress of the Sisters of Providence in Montreal. The statue stands outside the health system office in Renton, Wash., and at several other Providence ministries in the west.

Loretta Zwolak Greene, MA, CA

Archivist

Sisters of Providence, Mother Joseph Province

Providence Health & Services

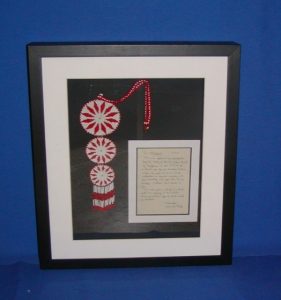

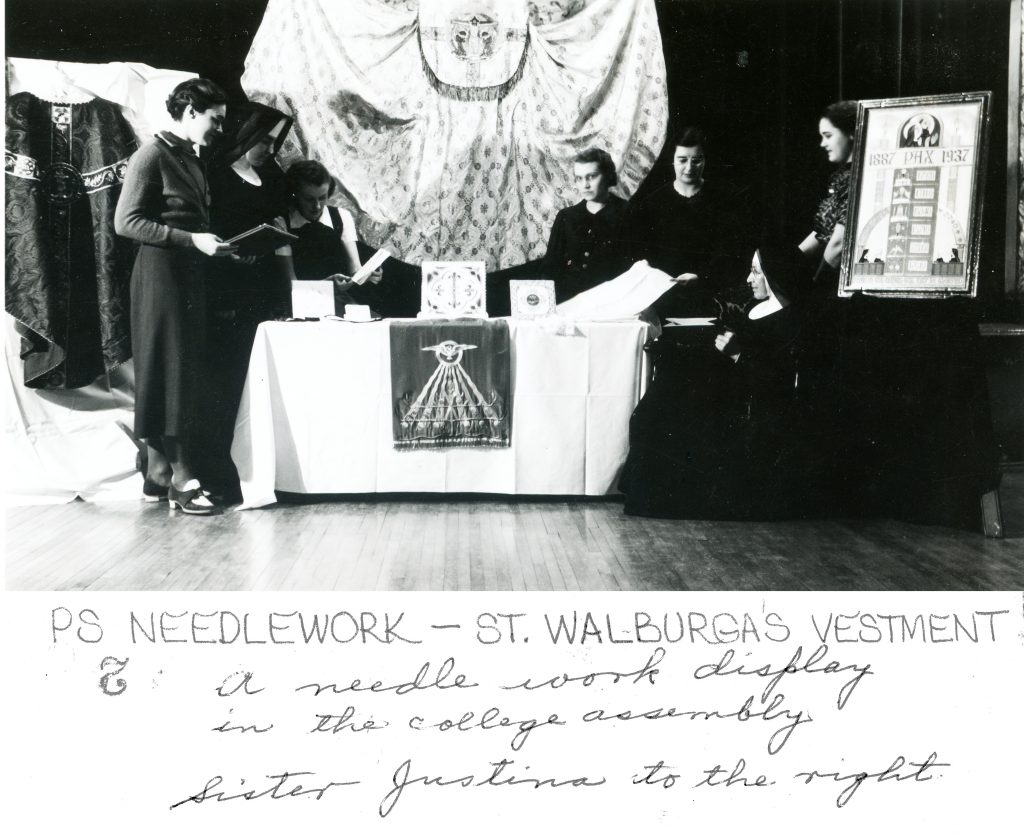

The Art/Needlework Department of Saint Benedict’s Monastery had its roots in St. Walburg Convent, Eichstatt, Bavaria, its motherhouse. Sister Willibalda Scherbauer, one of the first Benedictine sisters from Eichstatt to arrive in Minnesota in 1857, was trained in needlework as a young girl. She taught the first class in art needlework, specializing in fine embroidery, training many of her fellow nuns. The department was housed in a small attic room for many years, but with the great growth of Catholic churches and parishes in central Minnesota, the demand for the sisters’ needlework increased so much that more space was needed. In 1923 a new building was erected— St. Walburga’s Hall— which housed the department for the next 45 years. Over 45 sisters served in the needlework department between 1890 and 1968, many of them for 10-25+ years.

The Art/Needlework Department of Saint Benedict’s Monastery had its roots in St. Walburg Convent, Eichstatt, Bavaria, its motherhouse. Sister Willibalda Scherbauer, one of the first Benedictine sisters from Eichstatt to arrive in Minnesota in 1857, was trained in needlework as a young girl. She taught the first class in art needlework, specializing in fine embroidery, training many of her fellow nuns. The department was housed in a small attic room for many years, but with the great growth of Catholic churches and parishes in central Minnesota, the demand for the sisters’ needlework increased so much that more space was needed. In 1923 a new building was erected— St. Walburga’s Hall— which housed the department for the next 45 years. Over 45 sisters served in the needlework department between 1890 and 1968, many of them for 10-25+ years.

Sister Mary Kenneth was a strong advocate for the involvement of women in the field of computer science, particularly given the growing demand for computer experts and “information specialists.” There were, and are, jobs to be had and she saw no reason why women would not play a significant role in advancing computer science. She was supportive of working mothers, encouraging them to bring their babies with them to class as necessary.

Sister Mary Kenneth was a strong advocate for the involvement of women in the field of computer science, particularly given the growing demand for computer experts and “information specialists.” There were, and are, jobs to be had and she saw no reason why women would not play a significant role in advancing computer science. She was supportive of working mothers, encouraging them to bring their babies with them to class as necessary.